Don’t think about how a sociological experiment conducted in the 1950s in the state of Oklahoma in the United States might relate to the Survivor program or the way the fans of two fierce rivals like Fenerbahçe and Galatasaray form alliances in social events. Let me take you through the groundbreaking Robbers Cave experiment from that era, and you can draw your own conclusions. Of course, don’t forget to leave your comments, and I’d appreciate.

The story of the experiment’s organizer, Muzaffer Şerif, is also quite interesting. Born in Ödemiş, İzmir, during the Ottoman period, Şerif received his early education at İzmir American College. After completing his master’s degree in philosophy at Istanbul University in 1928, he started teaching psychology at Gazi University in Ankara. His academic career took a significant turn when he received a scholarship to study at Harvard University. Şerif moved to the United States, where he joined Yale University. After marrying Caroline Wood in 1945, he attempted to return to Turkey in 1947 but was unsuccessful. From that point on, he used the name Muzaffer Şerif in his academic works.

Over the years, Şerif accelerated his research in social psychology, conducting two major experiments. The most famous of these was the Robbers Cave experiment, which later inspired reality shows focusing on nature and competition between groups. However, to truly understand the purpose of this experiment, it is important to first look at the “Realistic Conflict Theory.” According to this theory, groups compete for limited resources, such as money, political power, or social status. For instance, a war between two countries could be fought over an oil resource. The intensity of the conflict varies depending on the value of the desired position or wealth.

Şerif decided to turn this theory into an experimental study. Since simulation systems or computer-based tests did not exist at the time, he had to test the theory by observing real-world behavior. In those days, simulations and artificial intelligence had not been discovered, so the experiment had to be carried out in the field.

For the experiment, 22 children, aged 11-12, who did not know each other before, were selected from middle-class and relatively religious families in Southeast Oklahoma. These children were split into two equal groups, unaware of each other, and the three-phase experiment began. In the first phase, the children were given one week to form bonds within their own groups. During this time, they developed a hierarchy of status and behavioral norms. They decided who would be the leader, who would be shy, and who would be aggressive. A name was also chosen for each group: one was called “Rattlers” and the other “Eagles.” At the end of this phase, the children had begun to know each other’s groups, and interestingly, despite not having interacted with each other, they started making hostile comments about the other group. At this point, a “us” vs. “them” mentality emerged, and the first phase of the experiment was complete.

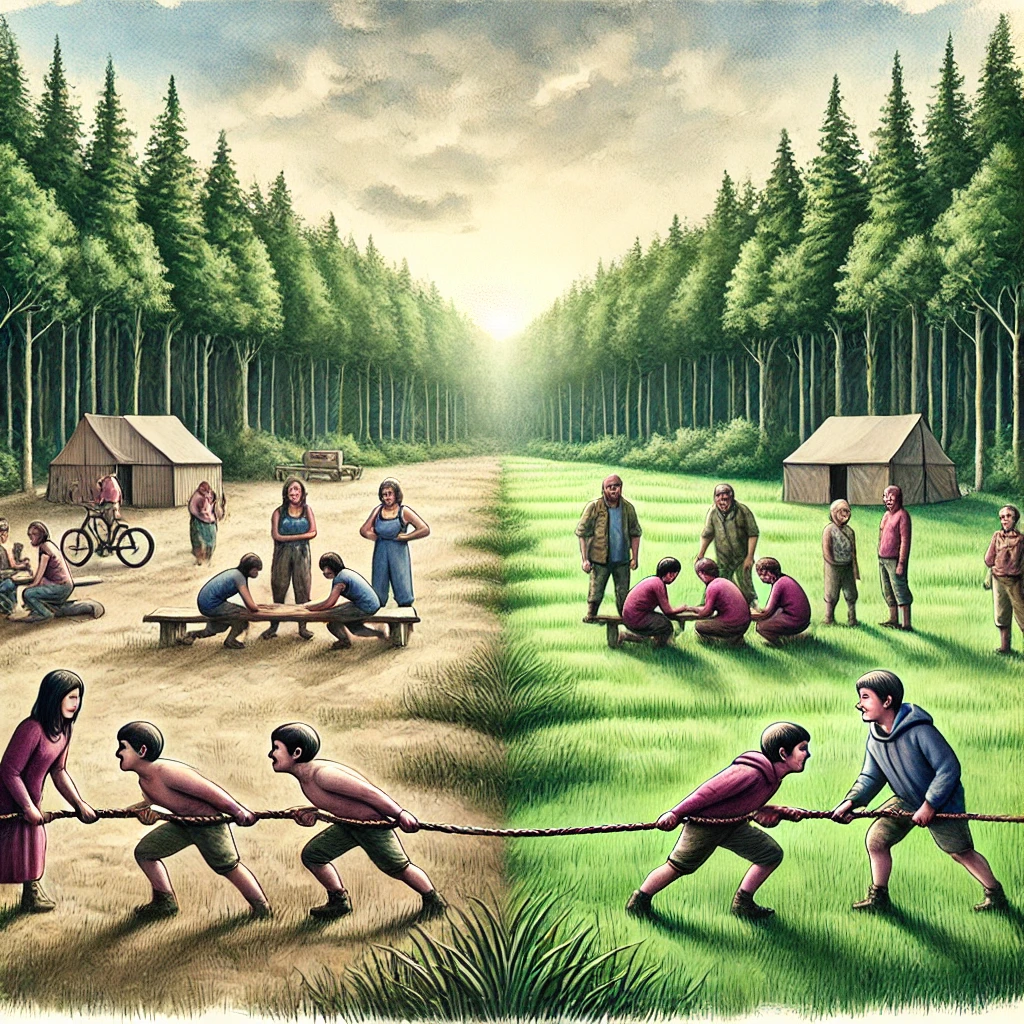

In the second phase, the researchers started organizing competitions between the two groups. This phase lasted about a week and included competitive activities like tug-of-war, tent building, and baseball. During this phase, the researchers began intervening in the experiment, observing the outcomes. On one occasion, one group was deliberately made late for lunch so that the other group had to wait until the first group finished their meal. This created an injustice, which increased tensions. Additionally, the “Rattlers,” having won the tug-of-war, planted their flag on the field. In retaliation, the “Eagles” group burned the flag. The next day, the “Rattlers” raided the “Eagles” team’s cabin, overturned their beds, and took some of their belongings.

The “Eagles” won some of the competitions, but after losing, the “Rattlers” group refused to accept their defeat gracefully and escalated the situation. The children began to exhibit aggressive behavior. Although there was no physical harm due to adult supervision, the tension was rising. As things escalated, such as filling socks with rocks, the experimenters intervened, and after a two-day break, they moved on to the third phase of the experiment.

The third phase involved activities designed to bring the two groups together and reduce their hostility. They started with simple joint activities like watching a movie together and collecting plants. However, contrary to expectations, no positive changes occurred between the groups. Subsequently, more challenging scenarios were introduced. The children were told that the camp’s water supply was blocked and they needed to solve the problem together. After working together for about an hour, they managed to resolve the issue. Another scenario involved the need to raise money for a film that the camp’s budget could not cover. The children pooled their money and solved the problem. Finally, another task was to get the food truck out of the mud, which they successfully completed by working together.

By the end of the experiment, the animosities between the children had disappeared, and friendships had formed through their collaborative efforts. When it was time to leave the camp, the children, who had previously been enemies, sat together. At the end of the experiment, the “Rattlers” used the $5 prize they had won to allow all their friends to have fun together. The process of solving a common problem had a profoundly positive effect on the group members.

Şerif and the other researchers made sure that the children in the experiment shared similar ethnic, religious, familial, and socioeconomic backgrounds. This allowed them to observe that the conflict between the groups did not arise from their differences but from the structures and hierarchies they created within themselves. The group structures observed in the experiment could be likened to countries in the world. Each country has its own rules, principles, and borders. These internal structures create the roots of conflicts between countries.

In conclusion, the way to resolve hostility between groups is to unite around a common goal. In this experiment, what brought the “Rattlers” and “Eagles” together was their desire to solve common problems. This is a situation that can often be observed in real life: due to an external factor, former enemies can come together and work on a shared problem.

The Robbers Cave experiment also sheds light on the fundamental dynamics of reality shows like Survivor. The pattern of group formation, competition, and goals operates in the same way. The outcomes in real life and shows may be similar. However, the key takeaway is how, in situations where different groups come together, we can unite by focusing on a common goal.